When Do Babies Start Sitting in High Chairs

C omfortably seated in the fertility dispensary with Vivaldi playing softly in the background, y'all and your partner are brought coffee and a folder. Inside the folder is an embryo menu. Each embryo has a description, something like this:

Embryo 78 – male

No serious early on onset diseases, merely a carrier for phenylketonuria (a metabolic malfunction that can crusade behavioural and mental disorders. Carriers just have one copy of the gene, so don't get the status themselves).

Higher than average risk of type 2 diabetes and colon cancer.

Lower than average risk of asthma and autism.

Night eyes, light dark-brown hair, male design baldness.

forty% chance of coming in the top one-half in Sabbatum tests.

There are 200 of these embryos to choose from, all fabricated by in vitro fertilisation (IVF) from you lot and your partner's eggs and sperm. And then, over to you. Which will you choose?

If at that place's any kind of future for "designer babies", it might expect something like this. It'southward a long way from the image conjured upward when artificial conception, and maybe even artificial gestation, were first mooted as a serious scientific possibility. Inspired by predictions almost the future of reproductive technology by the biologists JBS Haldane and Julian Huxley in the 1920s, Huxley'south brother Aldous wrote a satirical novel about it.

That book was, of form, Dauntless New Earth, published in 1932. Prepare in the year 2540, information technology describes a guild whose population is grown in vats in an impersonal central hatchery, graded into five tiers of different intelligence by chemical treatment of the embryos. In that location are no parents as such – families are considered obscene. Instead, the gestating fetuses and babies are tended by workers in white overalls, "their hands gloved with a pale corpse‑coloured condom", nether white, dead lights.

Brave New World has become the inevitable reference point for all media discussion of new advances in reproductive engineering. Whether it's Newsweek reporting in 1978 on the nascency of Louise Brown, the first "test-tube baby" (the inaccurate phrase speaks volumes) as a "cry round the brave new world", or the New York Times announcing "The brave new world of three-parent IVF" in 2014, the message is that we are heading towards Huxley'south hatchery with its racks of tailor-fabricated babies in their "numbered exam tubes".

The spectre of a harsh, impersonal and disciplinarian dystopia always looms in these discussions of reproductive command and choice. Novelist Kazuo Ishiguro, whose 2005 novel, Never Allow Me Go, described children produced and reared equally organ donors, final calendar month warned that thanks to advances in gene editing, "we're coming shut to the betoken where we tin, objectively in some sense, create people who are superior to others".

But the prospect of genetic portraits of IVF embryos paints a rather different motion-picture show. If it happens at all, the aim volition be not to engineer societies but to attract consumers. Should nosotros allow that? Even if we do, would a list of dozens or fifty-fifty hundreds of embryos with various all the same sketchy genetic endowments be of any use to anyone?

The shadow of Frankenstein's monster haunted the fraught discussion of IVF in the 1970s and 80s, and the misleading term "three-parent baby" to refer to embryos made by the technique of mitochondrial transfer – moving salubrious versions of the energy-generating jail cell compartments called mitochondria from a donor cell to an egg with faulty, potentially fatal versions – insinuates that there must be something "unnatural" about the procedure.

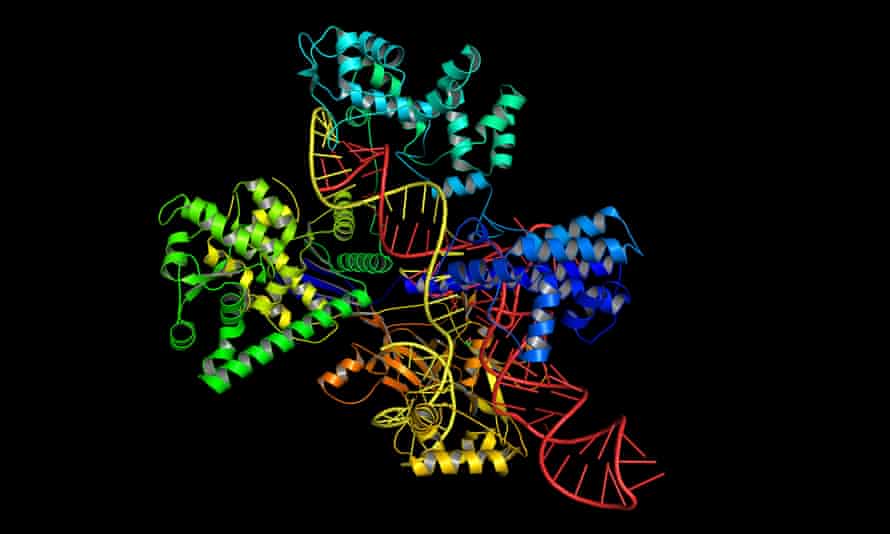

Every new advance puts a fresh spark of life into Huxley's monstrous vision. Ishiguro's dire forecast was spurred by the factor-editing method chosen Crispr-Cas9, adult in 2012, which uses natural enzymes to target and snip genes with pinpoint accuracy. Thanks to Crispr-Cas9, information technology seems likely that gene therapies – eliminating mutant genes that cause some severe, by and large very rare diseases – might finally bear fruit, if they tin can be shown to be safe for human being utilize. Clinical trials are now nether manner.

But modified babies? Crispr-Cas9 has already been used to genetically modify (nonviable) human embryos in Mainland china, to see if it is possible in principle – the results were mixed. And Kathy Niakan of the Francis Crick Found in the UK has been granted a licence past the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authorisation (HFEA) to use Crispr-Cas9 on embryos a few days old to find out more than nigh problems in these early stages of development that can pb to miscarriage and other reproductive issues.

Most countries take not notwithstanding legislated on genetic modification in human being reproduction, but of those that accept, all have banned it. The thought of using Crispr-Cas9 for homo reproduction is largely rejected in principle by the medical inquiry community. A team of scientists warned in Nature less than two years ago that genetic manipulation of the germ line (sperm and egg cells) by methods like Crispr-Cas9, even if focused initially on improving health, "could start us down a path towards non-therapeutic genetic enhancement".

Besides, there seems to be little demand for cistron editing in reproduction. It would exist a difficult, expensive and uncertain way to achieve what tin by and large exist achieved already in other means, particularly past simply selecting an embryo that has or lacks the gene in question. "Almost everything you tin can accomplish past gene editing, yous can accomplish by embryo selection," says bioethicist Henry Greely of Stanford University in California.

Because of unknown wellness risks and widespread public distrust of gene editing, bioethicist Ronald Green of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire says he does not foresee widespread use of Crispr-Cas9 in the next two decades, fifty-fifty for the prevention of genetic disease, allow alone for designer babies. However, Green does see factor editing actualization on the menu eventually, and perhaps not merely for medical therapies. "It is unavoidably in our future," he says, "and I believe that it will become one of the central foci of our social debates later in this century and in the century beyond." He warns that this might be accompanied by "serious errors and health problems as unknown genetic side effects in 'edited' children and populations brainstorm to manifest themselves".

For at present, though, if at that place'southward going to be anything even vaguely resembling the popular designer-infant fantasy, Greely says it will come from embryo selection, not genetic manipulation. Embryos produced by IVF will be genetically screened – parts or all of their DNA will be read to deduce which gene variants they bear – and the prospective parents volition be able to cull which embryos to implant in the hope of achieving a pregnancy. Greely foresees that new methods of harvesting or producing human eggs, along with advances in preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) of IVF embryos, volition make selection much more viable and appealing, and thus more common, in 20 years' time.

PGD is already used by couples who know that they carry genes for specific inherited diseases so that they tin identify embryos that do not have those genes. The testing, generally on iii- to five-24-hour interval-old embryos, is conducted in around 5% of IVF cycles in the US. In the Great britain information technology is performed under licence from the HFEA, which permits screening for around 250 diseases including thalassemia, early-onset Alzheimer'due south and cystic fibrosis.

As a way of "designing" your baby, PGD is currently unattractive. "Egg harvesting is unpleasant and risky and doesn't give you that many eggs," says Greely, and the success rate for implanted embryos is still typically about 1 in three. Merely that volition alter, he says, thank you to developments that will make human being eggs much more arable and conveniently available, coupled to the possibility of screening their genomes quickly and cheaply.

Advances in methods for reading the genetic code recorded in our chromosomes are going to arrive a routine possibility for every one of u.s.a. – certainly, every newborn kid – to take our genes sequenced. "In the next x years or and then, the chances are that many people in rich countries will have large chunks of their genetic data in their electronic medical records," says Greely.

But using genetic information to predict what kind of person an embryo would get is far more than complicated than is ofttimes implied. Seeking to justify unquestionably important research on the genetic footing of human health, researchers haven't done much to dispel simplistic ideas most how genes make u.s.a.. Talk of "IQ genes", "gay genes" and "musical genes" has led to a widespread perception that there is a straightforward i-to-ane relationship between our genes and our traits. In general, it's anything but.

At that place are thousands of mostly rare and nasty genetic diseases that tin can be pinpointed to a specific cistron mutation. Most more common diseases or medical predispositions – for example, diabetes, center disease or certain types of cancer – are linked to several or fifty-fifty many genes, can't be predicted with whatsoever certainty, and depend also on environmental factors such every bit nutrition.

When it comes to more complex things like personality and intelligence, nosotros know very little. Even if they are strongly inheritable – it's estimated that up to fourscore% of intelligence, as measured by IQ, is inherited – we don't know much at all nigh which genes are involved, and not for desire of looking.

At all-time, Greely says, PGD might tell a prospective parent things similar "there's a 60% adventure of this child getting in the top half at school, or a xiii% run a risk of being in the acme ten%". That'due south non much utilise.

We might practise better for "cosmetic" traits such as hair or eye color. Even these "plough out to be more complicated than a lot of people thought," Greely says, but as the number of people whose genomes have been sequenced increases, the predictive ability volition better substantially.

Ewan Birney, director of the European Bioinformatics Institute almost Cambridge, points out that, even if other countries don't cull to constrain and regulate PGD in the mode the HFEA does in the UK, it will be very far from a crystal brawl.

About anything you tin can measure for humans, he says, tin can exist studied through genetics, and analysing the statistics for huge numbers of people often reveals some genetic component. But that information "is not very predictive on an private footing," says Birney. "I've had my genome sequenced on the cheap, and it doesn't tell me very much. We've got to get abroad from the idea that your DNA is your destiny."

If the genetic footing of attributes similar intelligence and musicality is too thinly spread and unclear to make selection applied, then tweaking by genetic manipulation certainly seems off the menu besides. "I don't think nosotros are going to come across superman or a split up in the species any time soon," says Greely, "because nosotros just don't know plenty and are unlikely to for a long fourth dimension – or maybe for ever."

If this is all "designer babies" could mean fifty-fifty in principle – freedom from some specific just rare diseases, noesis of rather little aspects of advent, simply but vague, probabilistic information about more than general traits similar health, attractiveness and intelligence – will people go for information technology in large enough numbers to sustain an manufacture?

Greely suspects, even if it is used at commencement merely to avoid serious genetic diseases, nosotros need to showtime thinking hard about the options we might be faced with. "Choices will be made," he says, "and if informed people do not participate in making those choices, ignorant people will make them."

Green thinks that technological advances could brand "blueprint" increasingly versatile. In the side by side twoscore-50 years, he says, "we'll offset seeing the use of factor editing and reproductive technologies for enhancement: blond pilus and blue eyes, improved able-bodied abilities, enhanced reading skills or numeracy, and so on."

He'southward less optimistic almost the consequences, saying that we will then see social tensions "as the well-to-exercise exploit technologies that make them even better off", increasing the relatively worsened health status of the world's poor. As Greely points out, a perfectly feasible 10-20% improvement in health via PGD, added to the comparable reward that wealth already brings, could lead to a widening of the health gap betwixt rich and poor, both within a guild and betwixt nations.

Others dubiety that there volition be any nifty demand for embryo selection, especially if genetic forecasts remain sketchy about the about desirable traits. "Where there is a serious problem, such as a deadly condition, or an existing obstacle, such as infertility, I would not exist surprised to see people take advantage of technologies such equally embryo selection," says law professor and bioethicist R Alta Charo of the University of Wisconsin. "Merely we already have testify that people do not flock to technologies when they can conceive without assistance."

The poor have-up of sperm banks offering "superior" sperm, she says, already shows that. For most women, "the emotional significance of reproduction outweighs any notion of 'optimisation'". Charo feels that "our ability to love one another with all our imperfections and foibles outweighs any notion of 'improving' our children through genetics".

Nevertheless, societies are going to face tough choices about how to regulate an industry that offers PGD with an ever-widening scope. "Technologies are very amoral," says Birney. "Societies take to decide how to use them" – and different societies will brand different choices.

1 of the easiest things to screen for is sex. Gender-specific abortion is formally forbidden in well-nigh countries, although it still happens in places such as Prc and India where there has been a potent cultural preference for boys. But prohibiting selection by gender is another matter. How could it fifty-fifty be implemented and policed? Past creating some kind of quota system?

And what would pick against genetic disabilities practise to those people who have them? "They have a lot to exist worried about here," says Greely. "In terms of whether society thinks I should take been born, but also in terms of how much medical research there is into diseases, how well understood it is for practitioners and how much social support in that location is."

Once selection beyond abstention of genetic disease becomes an option – and information technology does seem probable – the upstanding and legal aspects are a minefield. When is it proper for governments to coerce people into, or prohibit them from, particular choices, such as not selecting for a disability? How can i remainder individual freedoms and social consequences?

"The most important consideration for me," says Charo, "is to be clear most the distinct roles of personal morality, by which individuals decide whether to seek out technological assistance, versus the office of regime, which can prohibit, regulate or promote technology."

She adds: "Too often nosotros discuss these technologies as if personal morality or particular religious views are a sufficient ground for governmental action. But one must footing government action in a stronger set of concerns almost promoting the wellbeing of all individuals while permitting the widest range of personal freedom of conscience and selection."

"For better or worse, homo beings will non forgo the opportunity to take their evolution into their ain hands," says Greenish. "Will that make our lives happier and better? I'm far from certain."

Easy pickings: the hereafter of designer babies

The simplest and surest mode to "pattern" a baby is not to construct its genome by choice'n'mix gene editing but to produce a huge number of embryos and read their genomes to find the one that virtually closely matches your desires.

2 technological advances are needed for this to happen, says bioethicist Henry Greely of Stanford University in California. The production of embryos for IVF must become easier, more abundant and less unpleasant. And gene sequencing must be fast and cheap enough to reveal the traits an embryo will accept. Put them together and you accept "Easy PGD" (preimplantation genetic diagnosis): a cheap and painless mode of generating large numbers of homo embryos and so screening their unabridged genomes for desired characteristics.

"To get much broader use of PGD, you need a amend manner to get eggs," Greely says. "The more eggs you can get, the more bonny PGD becomes." Ane possibility is a i-off medical intervention that extracts a piece of a adult female'due south ovary and freezes it for future ripening and harvesting of eggs. It sounds desperate, but would not be much worse than electric current egg-extraction and embryo-implantation methods. And information technology could give access to thousands of eggs for futurity use.

An fifty-fifty more dramatic approach would be to grow eggs from stem cells – the cells from which all other tissue types can be derived. Some stem cells are present in umbilical blood, which could exist harvested at a person's nascence and frozen for later employ to grow organs – or eggs.

Even mature cells that have advanced across the stem-jail cell stage and become specific tissue types can exist returned to a stem-cell-similar land by treating them with biological molecules called growth factors. Concluding October, a team in Japan reported that they had made mouse eggs this way from skin cells, and fertilised them to create apparently good for you and fertile mouse pups.

Thanks to technological advances, the toll of human whole-genome sequencing has plummeted. In 2009 it cost around $fifty,000; today it is most like $i,500, which is why several private companies can at present offer this service. In a few decades it could cost just a few dollars per genome. Then it becomes viable to think of PGD for hundreds of embryos at a time.

"The science for prophylactic and effective Easy PGD is likely to be some time in the adjacent 20 to 40 years," says Greely. He thinks information technology will and then get common for children to exist conceived through IVF using selected genomes. He forecasts that this volition pb to "the coming obsolescence of sex" for procreation.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2017/jan/08/designer-babies-ethical-horror-waiting-to-happen

0 Response to "When Do Babies Start Sitting in High Chairs"

Post a Comment